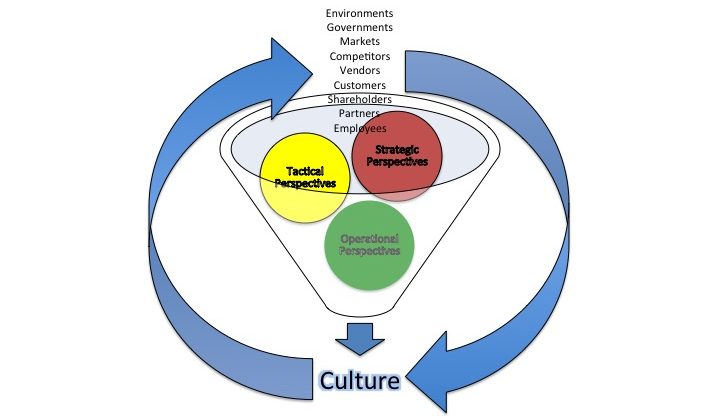

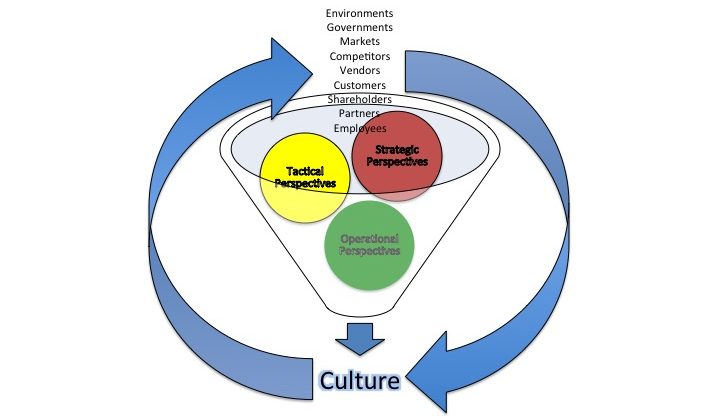

In my opinion, culture is about people but it is also about processes, products, services and technologies.

In my opinion, culture is about people but it is also about processes, products, services and technologies.

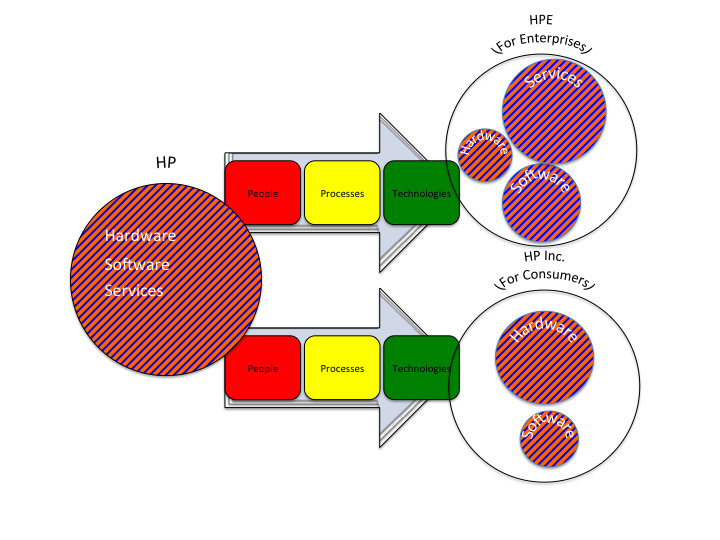

A year ago Hewlett Packard (HP) decided that it was going to split into two companies. This decision became real last week when HP officially split into HP Inc. and Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE) as announced by Meg Whitman on her LinkedIn post. The main reason given for this split was the focus. HP Inc. would focus on selling consumer products such as personal computers and printers. HPE would focus on selling enterprise products, enterprise software and enterprise services such as cloud computing, big data, cybersecurity to improve operations.

It seems that on the surface the announcement of the split of HP into HP Inc. and HPE has received a mixed bag of optimism and skepticism from different corners of the tech industry. On the optimistic side, this is a good move since it would help these companies focus on their core competencies and provide focused customer service and client experience. On the skeptical side, this is a little too late since the tech industry has been moving from merely selling computer products to selling more technology software and services for at least 20 years.

If we observe the tech industry from a modern economics lens we would find that this split is not something that is novel but it is very predictable. From a modern economics lens, the ‘primary sector’ for the tech industry focused on hardware and products, the ‘secondary sector’ for the tech industry focused on software and the ‘tertiary sector’ for the tech industry focuses on technology services. What is interesting is that this split lets HP Inc. focus on the ‘primary tech sector’ for consumers while HPE focuses on both the ‘secondary tech sector’ and the ‘tertiary tech sector’ simultaneously for enterprises. Eventually, though, HPE would increase its focus on the ‘tertiary tech sector’ since the margins are much better in services as compared to just products and software. In order for HPE to become a bigger player in the services market, they should consider the following:

|

Currently |

In the Future |

| Who is leading the services division?

| Who should be leading the services division? |

| What processes are being followed to provide services? | What processes should be followed to provide services? |

| Where the mix of tech and non-tech services are being provided? | Where a mix of tech and non-tech services should be provided? |

| When are services bundled with hardware and software? | When should services be bundled with hardware and software? |

| Why standalone services are provided? | Why should standalone services be provided? |

HPE leadership has to realize that any organizational splits are not without consequences. These consequences could entail: (1) Stocks becoming more volatile as any budget cuts with client enterprises could affect the bottom line, (2) Competitors might be able to provide the same level of service at a cheaper cost with better client experiences and (3) Lack of optimized processes with no flexibility to adjust for enterprise clients needs could reduce overall reputation of HPE.

One of the ways to address the above-mentioned split issues would be to create independent mock enterprise client teams that would rate how easy or difficult it was to deal with HPE in light of changing economic conditions, client experiences and efficient and effective processes. These independent mock enterprise client teams would be used to further refine HPE and put itself in the shoes of its enterprise clients.

In the video below on CxO Talk, I asked Chris Hjelm, Executive Vice President and Chief Information Officer (CIO) of Kroger, how do they decide which IT projects are strategic versus operational.

In my view, there are many layers to look at when it comes to deciding what is strategic and what is operational for IT projects. For starters, IT strategic project have to be directly tied to overall strategic objectives of the entire organization. This means is that if an IT project is not providing value in terms of efficiency and/or effectiveness to improve organizational operations, then it is not strategic enough.

It should also be noted that as time progresses, certain Strategic IT would become Operational IT.

A couple of weeks ago Alphabet Inc. emerged as a parent holding company of Google as announced by Larry Page on Google’s blog. The two main reasons given for this move is to make the company cleaner and more accountable. By cleaner, it means that products that are not related to each other would become separate wholly-owned subsidiaries of Alphabet Inc. which includes Google, Calico, X Lab, Ventures and Capital, Fiber and Nest Labs. By becoming more accountable, it means that leaders of these wholly-owned subsidies would be held to even higher standards and accountability of where the money is and should be spent. This move would help Wall Street understand that Alphabet is willing and structurally capable of going into areas that are unrelated.

It seems that on the surface the announcement of creating Alphabet Inc. has deemed to be a good move as many pundits and professors have pointed out ever since its emergence. The reasons of cleanliness and accountability are great for internal purposes. However, if we dig a little deeper we would find that there are external purposes that are at play here as well. Firstly, due to Alphabet Inc.’s cleaner approach, mergers and acquisitions of unrelated industries would become much easier and thus accountability of each wholly-owned subsidiaries would be justifiable to Wall Street. Secondly, Alphabet Inc. would now be able to enter into industries or create new industries altogether. This move could mean that Alphabet Inc. could also be the next big 3D manufacturer of electronic equipment or even the next Big Bank that finally removes paper-based transactions. While both of these examples are interesting and achievable due to Alphabet Inc.’s deep pockets. In order for Alphabet Inc. to really disrupt or create new industries, strategic consideration should be taken into the following:

|

Currently |

In the Future |

| Who is leading the organization(s)?

| Who should lead the organization(s)? |

| What processes are being followed? | What processes should be followed? |

| Where are the products and services being deployed? | Where products and services should be deployed?

|

| When do people, processes, technologies, products, and services disrupt/create markets? | When should people, processes, technologies, products, and services disrupt/create markets? |

| Why already bought companies make sense? | Why companies should be bought? |

Alphabet Inc.’s leadership also has to realize that any organizational structural changes are not without consequences. These consequences could entail: (1) Stocks could become more volatile as even any slightly negative news concerning the wholly-owned subsidiaries could affect Alphabet Inc. stocks, (2) Due to autonomy and fiefdom creation, collaboration across people, process, technologies, products and services among the wholly-owned subsidiaries could be compromised and (3) There could be rise of duplicative functional teams (e.g., HR, Finance, etc.) across all wholly-owned subsidiaries thus taking resources away from core business pursuits.

One of the ways to address the above-mentioned conglomerate issues would be to create a task force with enough teeth within Alphabet Inc., and cross-organizational teams across all wholly-owned subsidiaries who can help find and remedy these issues. This task force and its teams could be similar to internal consultants whose lessons learned and methodologies could help Alphabet Inc. become more efficient and effective. Perhaps these practices could also open the door for Alphabet Inc. to dominate the Management Consulting industry as well.

You must be logged in to post a comment.